NC Policy Watch, a public policy organization, whose mission is “to change the way our elected officials debate important issues facing North Carolina and, ultimately, to improve the quality of life in the state”, has raised concerns about the location and safety of the new Aberdeen Elementary School on Highway 5. NC Policy Watch is a project of the North Carolina Justice Center. The following article is reprinted with permission.

On the edge of Aberdeen lay a lovely tract of land that was easy to miss while speeding down Highway 5. Stippled with young to middle-aged pine trees, it historically had been used for timbering, but now the landowner, BVM Properties, was ready to sell.

Where BVM saw an opportunity to offload land, which some who knew the town’s history viewed as undesirable, Moore County School District officials envisioned possibility: The 22 acres would accommodate a new and larger elementary school for Aberdeen kids. It would be filled with light and equipped with modern technology, and plenty of outdoor space where its 800 children in Pre-K through fifth grade could play.

What a contrast it would be to the current Aberdeen Elementary and Primary schools. Built in the 1940s, when Aberdeen was formally segregated, the schools are cramped, dilapidated and threadbare. They remind teachers, staff and students – most of whom are from communities of color – of enduring inequality.

But this land and this school would be different. Better yet, the property was cheap: $9,000 an acre. It was the first and only offer school district administrators considered.

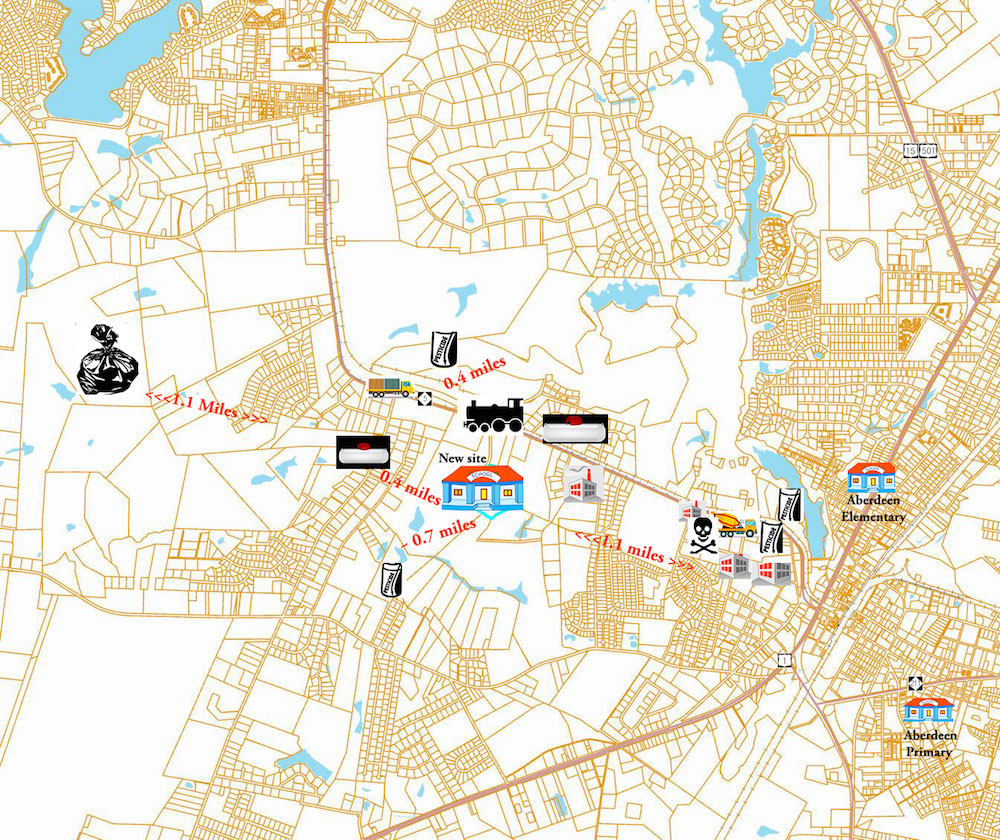

The land was cheap for a reason. It is sandwiched between two Superfund sites where pesticides were dumped for 50 years. It is located next to an industrial area and within a mile of 10 air pollution sources.

Yet district officials, many of whom are familiar with the history of pesticide dumping in Aberdeen, insist the site is safe. They are basing their confidence on Phase I environmental assessment from engineering firm Building & Earth, which the district hired to analyze the site. “Everything they looked at didn’t reveal anything wrong with the property,” said John Birath, director of operations for Moore County Schools.

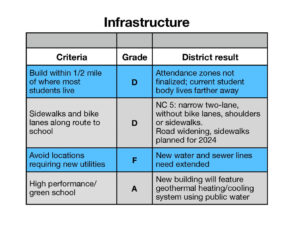

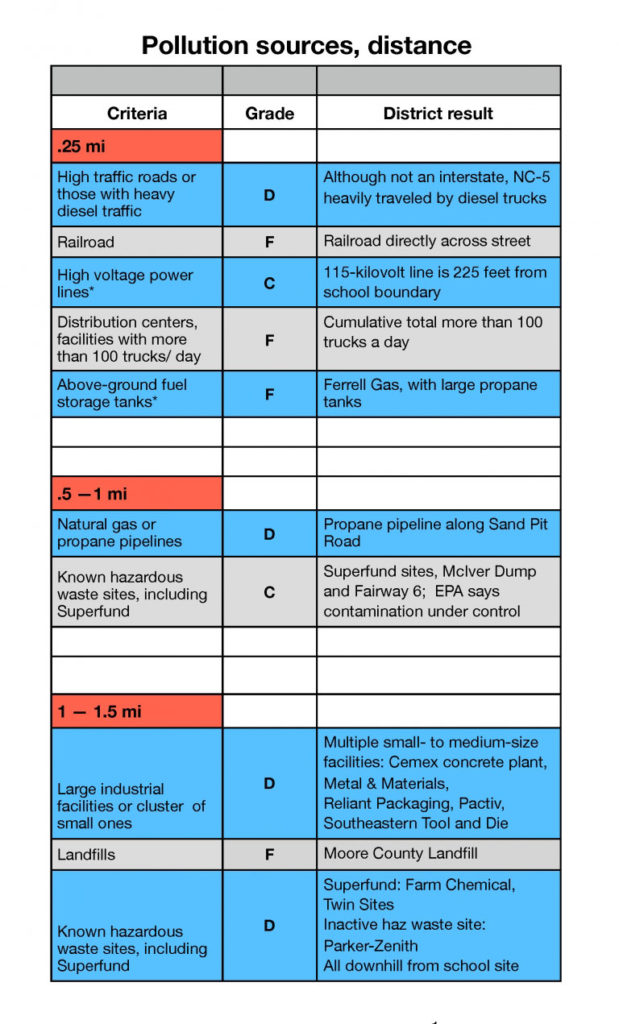

But a review of that assessment shows that it relies primarily on historical documents and “visual inspections.” Independent testing, which would be part of a Phase II assessment, isn’t required unless records indicate there could be pollution on the property. Nor did the assessment consider many other pollution sources. The school is scheduled to open next fall, and construction has already begun, even though by locating the new school on this property, district officials defied nearly every EPA recommendation – and some state guidelines – for siting schools: It is within a mile of a railroad, a highway with heavy diesel truck traffic, an industrial zone, a propane gas facility, a propane pipeline, four Superfund sites, and several small manufacturing facilities. There will be no sidewalks or bike lanes for at least four years. The district never released the environmental assessment for public comment.

You’re reproducing inequality

As part of a $103 million bond, the district is building several other schools, but none of them in areas this polluted. In Southern Pines, which is north of Aberdeen, the district is spending $82,000 an acre – upward of $1 million – for a new elementary school with no obvious or documented contamination sources. Whereas 80 percent of students attending Aberdeen schools qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, a little more than half of Southern Pines Elementary students do. The North Carolina average is 59 percent, according to state data. Half of students who attend Southern Pines are from communities of color; at Aberdeen, that figure is two-thirds.

The ramification

The ramifications of exposing school children, especially those who are low-income, to pollution can be far-reaching and long-lasting. Assistant professor Claudia Persico is a researcher at American University who studies the effects of industrial pollution on children. Her studies have found that students exposed to air pollution have lower test scores and higher rates of absenteeism and suspensions compared to those who were not exposed.

Claudia Persico is an assistant professor at American University. She has studied the effects of industrial pollution on school-age children. She will speak on that topic Monday, June 17, at 5 p.m. at NC State, SAS Hall, Room 1102.

Claudia Persico is an assistant professor at American University. She has studied the effects of industrial pollution on school-age children. She will speak on that topic Monday, June 17, at 5 p.m. at NC State, SAS Hall, Room 1102.In some instances, these students earn lower wages over their lifetime, perpetuating the cycle of poor health and generational poverty.” Air pollution hurts academic performance” Persico said. “You’re reproducing inequality.”

Finding the right land in Moore County is more difficult than it looks by consulting a map. Much of the vacant land is consumed by golf courses, which are popular because of Pinehurst’s reputation as a golfing mecca that has hosted multiple U.S. Open tournaments. Growth in the northern part of the county is slower than in the southern part, such as Aberdeen, where military families are streaming in.

As part of a massive overhaul, in 2014 the school district hired the Operations and Research Education Laboratory at NC State University to suggest the best sites for several new schools. OREd, as it’s known, examined demographic and growth trends – not environmental factors. As illustrated by a series of large circles on a map, OREd recommended a site on NC-5, across from the old Pit Links Golf Course. “It was an optimal site location for a new school,” Birath said. “It was smack dab in the middle of the circle.”

Enter BVM Properties, which owns a lot of land in Moore County. BVM stands for Bernice V. Martin, widow of Robert Martin, a renowned eye surgeon in Pinehurst. Both have since died, and the property company is now managed by their son, also named Robert. BVM had been negotiating with a local residential developer, Birath said, “but the developer stepped away for a period of time.” During that hiatus, the broker for the property approached the school district. “We found that it was a very promising site,” Birath said.

The EPA siting guidelines, which are voluntary, are designed to protect students from pollution. The district, though, did not consult them, said Board of Education member Bruce Cunningham. He said he didn’t know about the guidelines until Policy Watch emailed him a copy. Nonetheless, Cunningham said that based on a consultant’s report, “I have complete confidence that our students will be environmentally protected.”

Because children are smaller than adults, their immune systems are undeveloped, and they tend to put dirt in their mouths and to drink more water for their body weight, they are especially vulnerable to contamination. And children who come from underprivileged backgrounds, like most of those who attend Aberdeen Elementary and Aberdeen Primary, might also bear the environmental burdens of their neighborhoods. They’re more likely to reside near pollution sources and live in older homes that can present hazards, such as asbestos and lead paint. They might have asthma, poor nutrition or other health issues. When they attend school near pollution sources, these kids are never free of contamination.

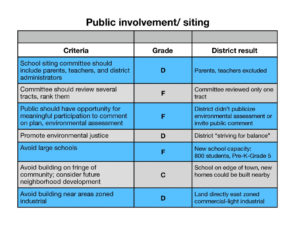

In choosing a new location, the EPA recommends that a school district convene a sitting committee, composed of administrators, school board members, teachers, and parents, to evaluate and rank several sites. But Moore County Schools convened only the members of the district staff and the superintendent. Nor did they consider any alternative sites.

The siting process failed other EPA litmus tests:

Transparency – In response to concerns about the proximity of former pesticide dumps to the site, the district paid $9,000 for an environmental assessment, conducted by Building & Earth. In that 2015 document, the firm acknowledged the assessment was not to be “construed to be comprehensive.” The EPA recommends that these assessments be released for “meaningful” public comment and engagement. The district did neither. Catherine Murphy, the spokeswoman for the district, said she disclosed it to the local media and that it was presented to the Board of Education at a May 2017 meeting. She said she also provided the document “whenever it was requested.” But people can’t ask for what they don’t know exists.

Industrial areas and landfills – The EPA recommends avoiding industrial areas, either large facilities or a cluster of small ones. The school site is within a mile of the Moore County Landfill. Carolina eRecyclers is 1/10 of a mile away. School property lies adjacent to a tract that is zoned “commercial-light industrial.” The manufacturing plants along NC-5 include Pactiv, which makes plastic trays, the Cemex concrete plant and Reliance Packaging, which extracts plastic films. Reliance operates six-to-seven days each week, 24 hours per day, according to state environmental documents. In April, the Department of Environmental Quality issued a Notice of Violation to the company for exceeding its air emissions of volatile organic compounds by 8 percent. The facility is permitted to emit up to 100 tons of these compounds, some of which are hazardous or toxic, but failed to adhere to that requirement. It was the second such violation since last August.

Fuel storage – Ferrell Gas sells and ships wholesale propane tanks by rail less than a quarter-mile from the school. An underground propane pipeline is less than a half-mile away.

Walkability – NC-5 is a main thoroughfare between Pinehurst and Aberdeen, and a primary route for heavy trucks entering and leaving nearby manufacturing plants. A state Department of Transportation spokesman said the road will be widened to four lanes and include sidewalks, with construction bids opening in 2022. The road could be complete by 2024, four years after the school opens.

The EPA recommends locating schools in walkable neighborhoods – not on the edge of town, like the new Aberdeen site – because kids need to exercise. A Moore County health report card showed that 20 percent of schoolchildren between kindergarten and ninth grade are overweight. Birath said walkable schools are “a challenge” for rural areas. Children aren’t walking to school now, Birath said, even though a tunnel runs beneath US 1 to eastern neighborhoods. Most of the children travel by school bus or by car with their parents, adding to the load of air pollutants.

Hazardous waste sites – In addition to the Superfund pesticide dumps, another hazardous waste site, Parker-Zenith is about a mile from the school. Parker-Zenith repaired pumps for DuPont. The groundwater is contaminated with solvents and degreasers.

Stephen Lester is the science director for the Center for Health, Environment & Justice, which has published its own siting recommendations. Lester also was a member of the EPA siting guide task force and is critical of the final document because its guidelines are voluntary. “It has no teeth,” Lester said. “The EPA was reluctant to determine, from Washington, D.C., how to site schools. It couldn’t dictate it without being controversial.”

In response, the task force advocated for buffer areas between schools and pollution sources. But the science still can’t fully account for the cumulative effects on individuals with varying levels of vulnerability to contaminants. Lester recommends that schools track student health over time and that parents “ask hard questions about why their children are being exposed to toxic chemicals.”

In response, the task force advocated for buffer areas between schools and pollution sources. But the science still can’t fully account for the cumulative effects on individuals with varying levels of vulnerability to contaminants. Lester recommends that schools track student health over time and that parents “ask hard questions about why their children are being exposed to toxic chemicals.”

Lester said there’s no bright line between unacceptable risk and safety. “How do you determine what’s acceptable?” he said. “We don’t know, so we allow the exposure to continue. We do nothing.”

Air pollution, though, has not alarmed the community. Instead, the focus has centered on four Superfund sites that lie within a mile of the new school. From the 1930s until 1987, several companies blended and formulated commercial-grade pesticides, including the now-banned DDT, at a facility near NC-5 and Anderson Street in southwest-central Aberdeen. The companies spilled and dumped pesticides, bags and containers at that site – a site actually known as “Farm Chemicals” – and buried them by the ton at three offsite locations:

Across NC-5 near Pages Lake – the “Twin Sites” area;

On 10 acres near the Sixth Hole of the former Pit Golf Course – Fairway 6 – about 0.4 mile north of the new Aberdeen school site; and

The one-acre McIver Dump, near Patterson Branch Creek and less than a mile south of the school site.

Superfund sites are among the most polluted areas in the nation. The EPA intervenes in the cleanup when the responsible parties can’t be found, have gone out of business, or have declared bankruptcy.

The EPA cleaned up most of the contamination at the Aberdeen sites in the late 1980s, excavating tons of polluted soil at all of the dump sites to stem the groundwater contamination. The agency also encased soil, which had been burned to remove some but not all of the contaminants, in a lined, capped and covered landfill at Fairway 6. At McIver, the EPA planted poplar trees that absorbed the contaminated groundwater through their roots. (However, the EPA also routinely sprays herbicides near the trees to deter weeds, further polluting the soil.) One town well was closed and residents on private drinking water wells were connected to the public system.

It is true that the EPA has determined there is no short-term environmental or public health threat. Yet, since some contamination remains at the sites, the EPA conducts five-year reviews to determine the protectiveness of the cleanup. According to the agency’s latest five-year review, published in 2018, groundwater monitoring showed pesticide contaminant levels exceed state standards in four monitoring wells near the old McIver Dump; in some instances, the concentrations are increasing, according to EPA documents. Contaminated groundwater from the Twin Sites and Farm Chemicals locations continue to seep into Pages Lake, where there is a fish consumption advisory for mercury.

It is true that the EPA has determined there is no short-term environmental or public health threat. Yet, since some contamination remains at the sites, the EPA conducts five-year reviews to determine the protectiveness of the cleanup. According to the agency’s latest five-year review, published in 2018, groundwater monitoring showed pesticide contaminant levels exceed state standards in four monitoring wells near the old McIver Dump; in some instances, the concentrations are increasing, according to EPA documents. Contaminated groundwater from the Twin Sites and Farm Chemicals locations continue to seep into Pages Lake, where there is a fish consumption advisory for mercury.

The EPA has not declared the sites safe in the long-term. The new Aberdeen school will serve students for at least the next 30 to 40 years, and it’s reasonable to think that more cleanup could be required in the future. In the 2018 review, the EPA wrote that for long-term protection, there still needs to be a thorough review of the contaminants at McIver and Fairway 6, with a possible change in permissible levels.

Catherine Murphy of Moore County Schools said the district could not speculate on future cleanups.

District officials have assured the public that the school site will be untainted by groundwater contamination. The groundwater flows northeast, away from the school property, according to Building & Earth’s report. And since the school is at a higher elevation, it’s unlikely, but not impossible, that groundwater could reach the site.

But the same report acknowledges that it should not be “construed as comprehensive.” Many pages are merely cut and pasted from EPA reports. Nor has the district conducted soil sampling or groundwater testing at the new Aberdeen property itself. The district did pay $25,000 for a geotechnical survey and other tests to determine the suitability of the soil for the building and its geothermal system. (The district will pay most of the cost of running public water lines to the school, as well as a sewer extension. The geothermal system will use public water and be a closed system.)

County Commissioner Frank Quis has owned property near the school site for more than 20 years. He worked in a commercial building there, to no ill effect, he said. (He drank public water, not from a well.) Quis said his primary concern is that the school won’t have frontage; the small tracts along to the road could be developed according to their commercial-industrial designation. “I want people to see and be proud of their public schools,” he said.

County Commissioner Frank Quis has owned property near the school site for more than 20 years. He worked in a commercial building there, to no ill effect, he said. (He drank public water, not from a well.) Quis said his primary concern is that the school won’t have frontage; the small tracts along to the road could be developed according to their commercial-industrial designation. “I want people to see and be proud of their public schools,” he said.

Nor did the commissioners discuss pollution sources before approving funding for the Aberdeen school, money that was generated from a bond referendum. “You won’t find many sites that don’t have issues,” Quis said.

More than half the schools in North Carolina – 1,143 – are within a quarter-mile from at least one environmental hazard, according to a 2008 study by the UNC Institute for the Environment. Because the characteristics of school districts are so varied, no state regulations on school siting exist; like the EPA, the Department of Public Instruction has issued only voluntary guidelines.

“The precautionary principle” – proving a site is safe first rather than managing the hazards later – should prompt North Carolina, the UNC study says, “to establish school siting standards sufficient to ensure that schools are kept a safe distance from potential hazards.”

When the new $27 million school opens on its scheduled date in the fall of 2020, it will likely combine Aberdeen Primary, which enrolls 300 students in pre-K through the second grade, and Aberdeen Elementary, which has roughly 325 kids in grades 3 through 5.

These two schools have among the highest rates of economically disadvantaged students. The suspension rates are higher than the state average. The schools are low-performing, graded as “D,” although meeting growth expectations. Roughly two-thirds of students are from communities of color.

The EPA guidelines acknowledge school siting involves trade-offs, and it might be impossible for a district to find land that is free of potential pollution. But the agency also cautions that communities of color and low income bear an unfair environmental burden. “Studies highlight the disproportionate percentage of minority and low-income children that are exposed to multiple environmental hazards in close proximity to the schools they attend,” the guidelines read.

Attendance zones and districts are currently being redrawn, which could diversify the school, Murphy said. “We’re striving for balance. Our hope is to bring in students from surrounding communities.”

But the attendance zones are still in flux and highly controversial. Parents in nearby affluent Pinehurst, where the schools are mostly white and high-performing, could choose not to send their kids to Aberdeen, which is a short trip down NC-5. (The district is considering renaming the Aberdeen school to be more “inclusive” and less focused on geographic boundaries.)

The Aberdeen schools already are near the Farm Chemicals and Twin Sites Superfund areas, lying to the east instead of the west. Aberdeen Elementary is just feet from busy US 1. The fact is that many kids from underserved communities will continue to attend a school near multiple pollution sources.

O’Linda Watkins of the Moore County NAACP said the organization believes the students and staff of the new school have not been adequately notified of possible dangers. She is asking the group’s Environmental Justice Committee and Legal Redress Committee “to investigate this apparent oversight and to report to our next monthly gathering. We believe making our schools safe is not limited to trying to prevent crazed men from accessing weapons of mass terror and death; it also means we as a community must ensure our schools don’t expose its students and staff to chemical hazards, contaminants, and toxic substances that may pose risks to them. We trust this was a mere oversight by the Board.”

Stephen Lester of the Center for Health, Environment, and Justice said children’s health should take precedence over inexpensive land. And the entire siting process must be transparent and engage parents and caregivers. “I can understand the need to build a school,” Lester went on. “But it has to be balanced with children’s health. Parents can’t fight it if they don’t know.”

Article printed from NC Policy Watch: http://www.ncpolicywatch.comURL to article: http://www.ncpolicywatch.com/2019/06/14/pw-exclusive-moore-county-locates-new-elementary-school-near-pollution-hazardous-waste-sites-in-aberdeen/URLs in this post:[1] Image: http://www.ncpolicywatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/abedreen-lead-image-w-text.jpg[2] Superfund: https://www.epa.gov/superfund

[3] Building & Earth, : https://www.buildingandearth.com/

[4] Moore County Schools: https://www.ncmcs.org/

[5] Claudia Persico: https://www.american.edu/spa/faculty/cpersico.cfm

[6] Image: http://www.ncpolicywatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/claudia-persico.jpg

[7] Operations and Research Education Laboratory at NC State University: https://itre.ncsu.edu/focus/school-planning/ored/

[8] Image: http://www.ncpolicywatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/moore-inset-redux.jpg

[9] Image: http://www.ncpolicywatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/legend.jpg

[10] Center for Health, Environment & Justice,: http://chej.org/

[11] Image: http://www.ncpolicywatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Infrastructure.jpg

[12] Image: http://www.ncpolicywatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/public-involvement.jpg

[13] geothermal system: https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/heat-and-cool/heat-pump-systems/geothermal-heat-pumps

[14] Image: http://www.ncpolicywatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/pollution-sources.jpg

[15] Image: http://www.ncpolicywatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/aberdeen-thumbnail.jpg

Feature photo ~ Sandhills Sentinel.

Lisa Sorg, Environmental Reporter, joined N.C. Policy Watch in July 2016. She covers environmental issues, including social justice, pollution, climate change, and energy policy. Before joining the project, Lisa was the editor and an investigative reporter for INDY Week, covering the environment, housing, and city government. She has been a journalist for 22 years, working at magazines, daily newspapers, digital media outlets, and alternative newsweeklies.

Lisa Sorg, Environmental Reporter, joined N.C. Policy Watch in July 2016. She covers environmental issues, including social justice, pollution, climate change, and energy policy. Before joining the project, Lisa was the editor and an investigative reporter for INDY Week, covering the environment, housing, and city government. She has been a journalist for 22 years, working at magazines, daily newspapers, digital media outlets, and alternative newsweeklies.