The following article is courtesy of the Village of Pinehurst.

In recognition of the 125th anniversary of the Village of Pinehurst, over the next several months we will tell the story of how the Village came to be. Through a series of articles, we will document the unique events that led to the founding of our Village. Although the story of Pinehurst has been told in numerous publications and writings, we will focus on those events that are less well known, but fundamental in the creation of the Village 125 years ago.

This series will be updated monthly, so check back each month to find the latest installment.

Chapter 1: The Sandhills

How and why did a world-famous resort get its start in this location some 125 years ago? There are no majestic mountains with vistas, no beach or seashore to enjoy, no large bodies of water of any kind, no significant mineral deposits or assets to mine, not adjacent to a major metropolitan area, not a crossroad for commerce, the land could be considered generally uninteresting, of poor quality and it is off the beaten path.

To answer the question of how Pinehurst came into existence some 125 years ago requires an understanding of how multiple seemingly-unrelated factors came together: the topography and unique conditions of the area, the industry prevalent in this region, transportation options available during the second half of the 19th century, and most importantly, the life and will of one man: James Walker Tufts.

The Sandhills:

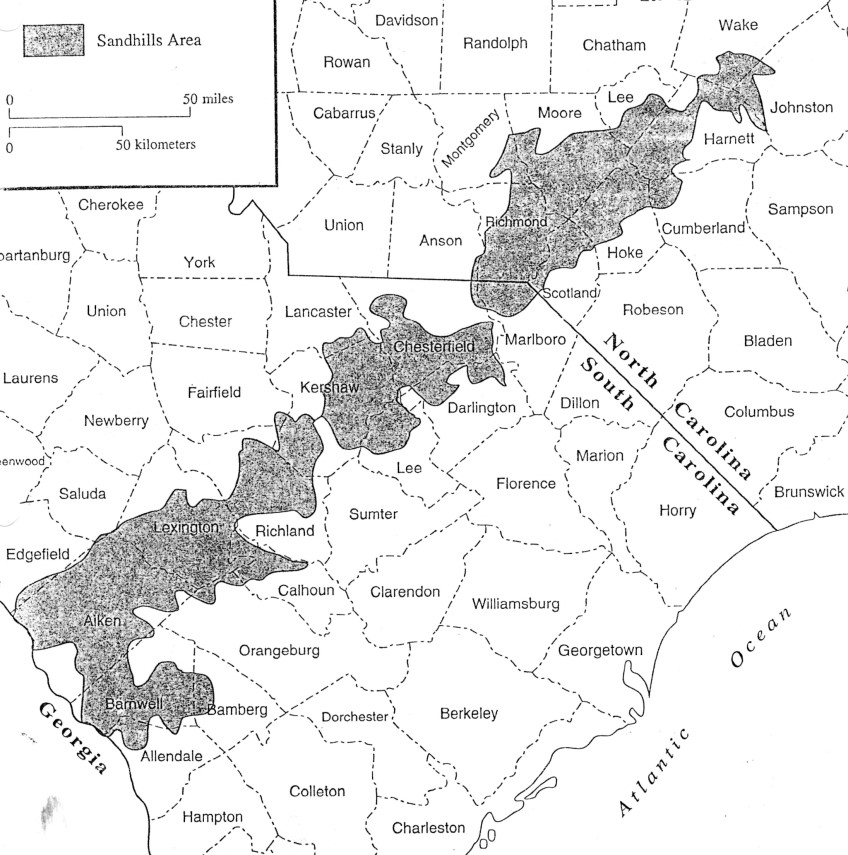

Moore County, founded in 1784 from its parent Cumberland County, has two very distinct topographies. The northern half of Moore County has generally clay and fertile soil originally forested by typical North Carolina hardwoods and conducive to farming. The southern part of Moore County is part of the Sandhills, a unique geological formation of primarily sand sediments that extend from Harnett and Lee Counties, North Carolina at the Northeastern end, southwestward to the South Carolina- Georgia border in Aiken and Barnwell Counties.1

In a book published in Raleigh in 1869, designed to attract northern money and emigrants, Moore County came in for modest notice:

Lands range from poor to good. Cotton, corn, sweet potatoes and pease (sic) grow well, and the grape may be raised extensively. It is well timbered with long leaf pine, but is rather inaccessible to market. Land can be bought very low.”2

The transition from the northern clay section of Moore County into the Sandhills can be abrupt and may take place in just a hundred yards or so. Here abounded one vast, gloomy forest of majestic long leaf pines, where one could travel from dawn to dusk on a pine needle carpet. Known in colonial and revolutionary days as the pine “barrens,” it was usually studiously avoided by the traveler on horseback, who would find no forage. 3

The Sandhills were formed in the Eocene Age as part of a large sea some 36 to 56 Million Years ago. The northernmost section of the Sandhills located for the most part in North Carolina is separated from the other formations further south in South Carolina and Georgia. This section is generally known as the “Pinehurst Formation.”

The two major geologic units of the Sandhills are the Upper Cretaceous age Middendorf Formation and the Eocene age Pinehurst Formation. The Pinehurst sediments were likely deposited about 45 million years ago as part of a large sea bed and coastline.1

Although there is some variety in deposits, sands found in lower Moore County are generally clean, well-drained soils. The well-drained nature of the Sandhills soil leads to low available water capacity and to rapid leaching of plant nutrients. As a result, the native vegetation of the Sandhills is limited to longleaf pine and loblolly pine with an understory of turkey and blackjack oak. This area was considered the least desirable part of the North and South Carolina Inner Coastal Plain as farming was difficult and unrewarding.

In many ways, these characteristics of the Sandhills became an asset: dry soil, well drained, and easily moved and sculpted for golf courses. In addition, the Sandhills are thought to possess a unique climate unlike that found in other areas since the sand quickly absorbs water and has some affect on the weather patterns as they move through the area.

In 1906 Leonard Tufts described the area and its climate:

“The Climate of Pinehurst is noted for its remarkable qualities,…. It is a well known scientific fact that wherever the long leaf pine grows the trees are productive of what is known as ‘ozone’. This section of North Carolina has more ozone in the air than in any place east of the Rocky Mountains. It is doubtful there is any place in the United States where persons brain-weary and nerve-worn rally or make as rapid progress toward health and vigor. The weather bureau in Washington has observed much warmer than points north and south in winter probably due to the sandy soil, which retains heat and, being a great absorbent of water, prevents evaporation that would otherwise cool the air.”4

So although the Sandhills seemed inhospitable and the land of little use, this unique environment was a significant reason why the area was touted as a special place for people with health conditions and became a factor in the selection of the area by James Walker Tufts as the site for his Village.

Chapter 2: The Longleaf Pine Forest the Tar, Turpentine, and Lumber Industry

The founding of Pinehurst was determined not only by the topology of the Sandhills, but also by the ecology of the area and the industry that sprung up to harvest the natural vegetation, primarily the longleaf pine.

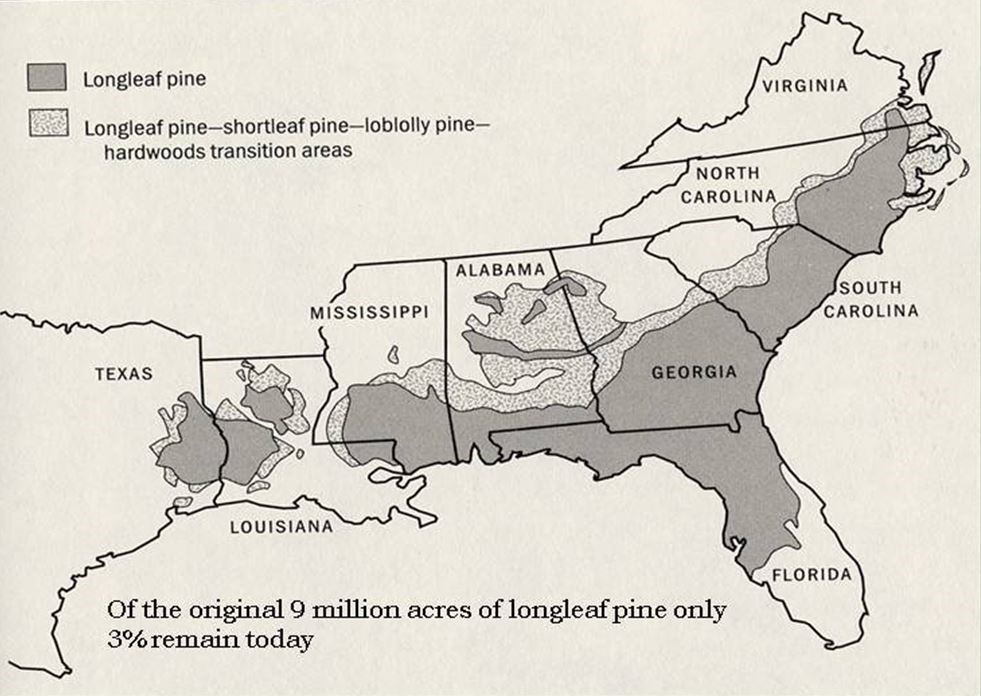

Longleaf pine is a pine species native to the southeastern US. The trees grow tall and straight, reaching heights of over 100 feet at maturity. At one time, a vast longleaf pine forest stretched from Virginia into Texas.

Two of the men on Sir Walter Raleigh’s first expedition in 1584 wrote about seeing pine trees on Roanoke Island:

There are those kinds of trees which yield them [pitch, tar, rosin, and turpentine] abundantly and great store. In the very same island where we were seated, being fifteen miles of length, and five or six miles in breadth, there are few trees else but of the same kind, the whole island being full. 1

The trees produce two types of cones: the pollen-bearing male cones and the seed-bearing female cones. They grow best in flat terrain and sandy soil that is nutrient poor.

Longleaf pines are adapted to experience periodic, low-intensity fires and these fires are necessary for longleaf forest health. The trees need a lot of light and have thick, fire resistant bark, so fires help keep longleaf forests open by burning off shade-producing plants and shrubs. The seeds are also unable to penetrate dense leaf litter to reach the ground, so removal of the ground cover by fire promotes germination while the ash provides valuable soil nutrients.

From the early days of colonization, the longleaf pine forests have been harvested for timber, but they also supported a “naval stores” industry. Tar, pitch, turpentine, and rosin are all products of pine, and the longleaf pine forests provided these essentials to merchant and naval ships.

Tar kept ropes and sail rigging from decaying, and pitch on a boat’s sides and bottom prevented leaking. For this reason, turpentine products were called ‘naval stores’. Turpentine was made into oil paint, which was used primarily to paint ships as well as the exteriors of buildings.

By the 1770s, North Carolina was producing 70 percent of the tar exported from the colonies and 50 percent of the turpentine. Naval stores were the colony’s most important industry.1

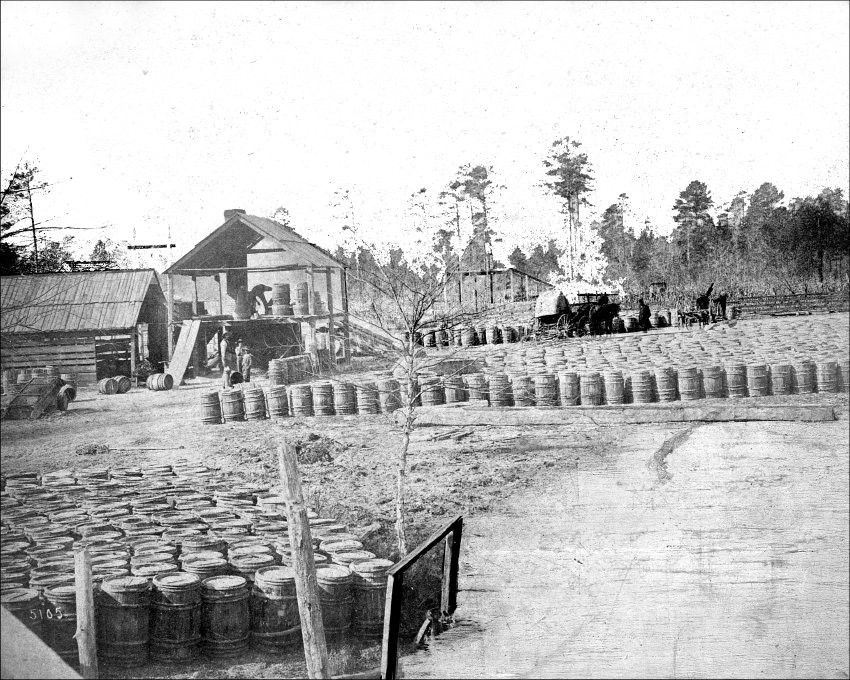

Turpentine is extracted from the longleaf pine by first cutting away the bark leaving the tree bare so the pine resin may be collected and then transferred into barrels for distilling.

At the distillery, the resin is turned into turpentine. As the tree became stressed, the limbs were buried in tar pits or kilns and burned so the tar would ooze out and be collected for sale. Then the tree was usually felled and sent off to lumber mills.

In an interesting twist, Frederick Law Olmsted, who later became the renowned landscape architect and provided the initial design for the Village of Pinehurst, while traveling in the South and reporting for the New York Daily Times (now The New York Times) from 1852 to 1857, recorded his observations of the turpentine forests and the people in the turpentine industry in the southern states.

Longleaf pines were destroyed by the technology of the day—scoring trees caused them to “bleed” and eventually killed them. A heavily-tapped forest could be depleted and destroyed in a decade. When that happened, the industry was forced to move on to find new forests to exploit.

By the time James Walker Tufts came to North Carolina to find a suitable location for his Village, the Longleaf Forest had been decimated. What was left was a wasteland of rotting stumps and branches littering the landscape with an occasional remaining stand of longleaf pines scatted here and there.

Photos courtesy of the Tufts Archives, Pinehurst NC.